by Sharon Thomas

Next year, Touchstones will be 40 years old. That remarkable milestone has led us to realize two things:

- We don't have a comprehensive, written document containing the history of the organization

(think Herodotus' Histories.) - We need to have a party next year.

Party planning is now beginning, but that first item has already become an important part of my job in navigating our work in schools.

I have been chatting for one hour each week with Touchstones co-founder and primary author, Howard Zeiderman, as I develop the unabridged narrative of our origins. Each week, Howard and I focus on a different topic (the influence of Howard's research on Touchstones, the evolution of each volume in the program, school programs in various parts of the world, etc.). Our conversations not only tap a wealth of information in Howard's brain but also ground me in the fascinating reasons behind and evolution of the entire organization. Several weeks ago, we touched on a topic that had been, literally, staring me in the face for years: the map illustrations on the cover of nearly every Touchstones volume.

Honestly, I think maps are pretty, and that's reason enough to have them on a cover. I have now learned that Howard had a much more important reason for their prominence—one that goes to the heart of every Touchstones program.

In our first few history sessions, Howard described how, as a college student in the late 1960s, he believed that multiple wars and massive societal upheaval were showing us that we need a different way to solve problems and navigate issues as people. He believed that real problems, real decisions, real changes, need to be decided in smaller, everyday discussions between individual human beings. We need to solve problems together in daily dialog and not allow some overriding world order to dictate solutions to us.

Howard saw many challenges with his theory. Humans don't do a good job of listening to each other. Discussions typically elevate the views of some (by gender, perceived power, recognized prominence) and silence the voices of others (the disenfranchised, the younger, the "other"). Most of us will say we want to have more collaborative and humanizing exchanges, but we've never been taught how to do that, whether at home, in school, or anywhere else. To engage in the type of discussions humanity needs, we each need a process that teaches us how to listen to each other, how to engage everyone's voice in the conversation, how to recognize our own limitations, understand what we gain from respecting diverse perspectives, and how to truly collaborate.

Thus, Touchstones was born.

As a college professor, Howard saw the need to empower all students to trust their own thinking. He didn't and still doesn't want students to revere texts by writers like Aristotle and Descartes. Instead, he wants them to decide for themselves what they think about the ideas in those texts. He doesn't want teachers and professors "guiding" students to the "right" answers; he wants students figuring things out for themselves. He doesn't want the text to be the main point of a discussion because he wants the way that students interact and work together to be the point. The texts are "touchstones" to spark discussions, but the human beings themselves are the point. They, too, with their knowledge and experience of the world, are equally legitimate touchstones.

So why the maps? In developing Touchstones, Howard metaphorically saw the Touchstones process as helping people to "map the world" for themselves instead of relying on the "maps" of those who have gone before us. Each map on a Touchstones or Touchpebbles cover is incomplete. None provides every piece of information an adventurer needs to travel there, but each gives information, some of which may be useful for navigating our way, and some may be inaccurate or simply wrong.

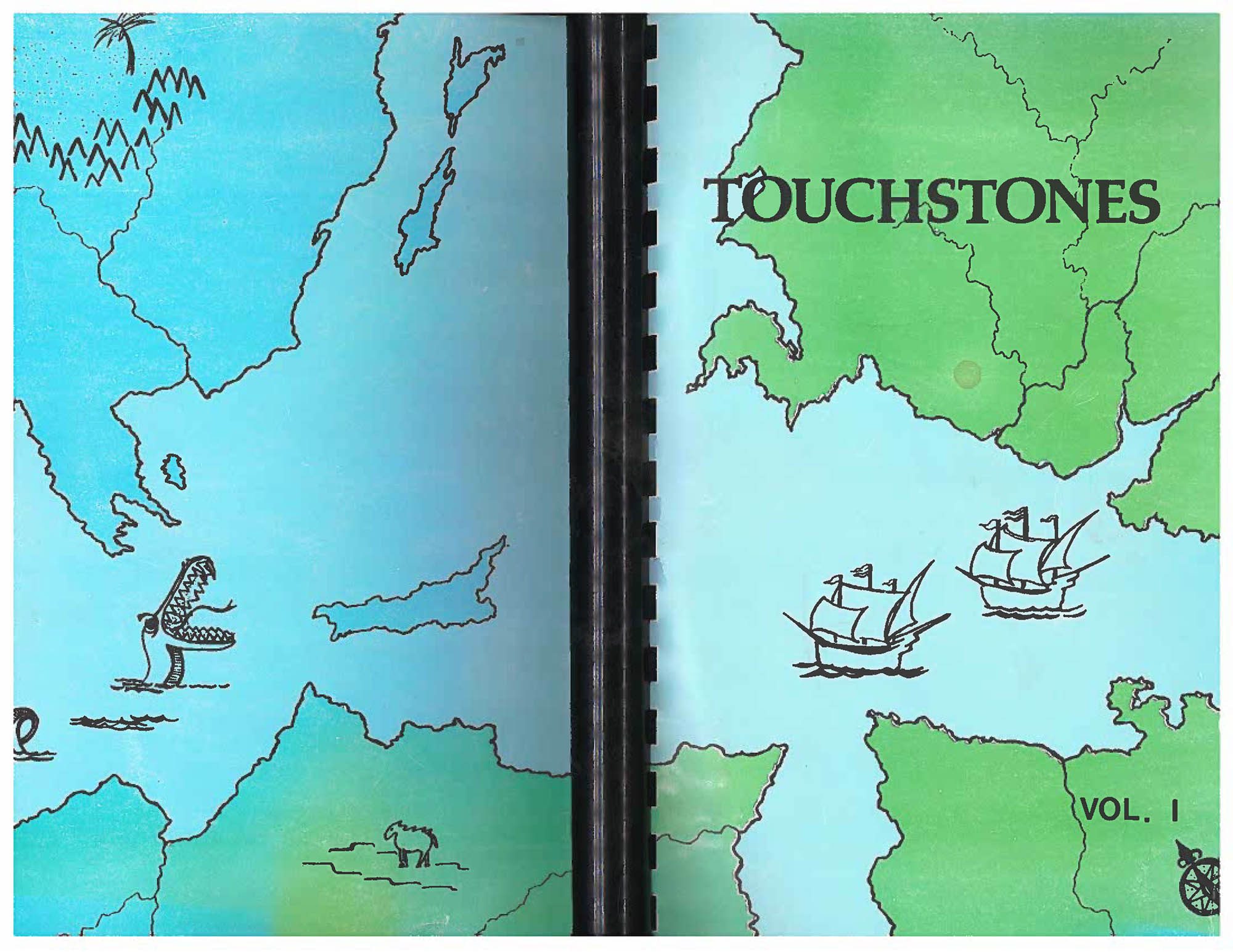

Nothing illustrates this view better than the map pictured here from the 1985 edition of Touchstones, Vol. 1, one that Howard drew himself (sea monster and all) (photo A). A close reading of this map gives the reader a great deal of information about this region, but there's a palm tree in the mountain range. Perhaps readers should question that. The sea monster itself may seem appropriate to some (depending on whether one believes in sea monsters), but is the scale of it accurate? Wouldn't a monster of that size generate several tsunamis a day? Perhaps readers (and fellow explorers) should question that as well.

Howard's map went the way of the Mosasaurus (or sea monster) decades ago, but the current Touchstones Vol. 1 still has a map on the cover (photo B). It may be more scientifically accurate than Howard's original map, but that doesn't mean it tells us everything we need to know. To fill in the gaps, to solve our problems as human beings, we need to work together, and we need to pool our collective knowledge, insights, and countless other communication and thinking skills. That means we need discussions that are collaborative, humanizing, and inclusive of everyone's perspectives.

All of our K-12 programs are specifically designed and scaffolded to support the empowerment of students as thinkers, collaborators, and leaders.

- Elementary school: Touchpebbles vols. A-C were created to reinforce that students' thinking (even that of 8-year-olds) is as valuable as anyone else's.

- Middle schools: Touchstones vols. A-C were created to show students that they are each capable of all kinds of thinking and problem-solving (historical, scientific, literary, and mathematical).

- High schools: Touchstones vols. I and II were created to encourage older students that, now that they understand that their thinking is valuable and they can navigate all kinds of issues, they need to map the world for themselves.

Touchstones doesn't just believe in the power and promise of children and adults to map the future for themselves. We've seen how our work in education harnesses each person's talents to advance themselves and others—how it builds an authentic community of learners, problem solvers, and leaders. The Touchstones mission to teach everyone how to engage in collaborative discussions with each other is an essential part of learning how to navigate the world together.

The next time you and your students pick up your Touchstones volumes, take a look at the map on the cover.

- What makes sense on this map? What doesn't make sense?

- What other types of information would be helpful for it to include? How could you access that information?

- Take the map apart intellectually and determine what's going on there together. And then spend time exploring how this analogy relates to what you're doing together in Touchstones.

Howard—and his sea monster—want you to.

Photo captions:

Photo A: The original cover of Touchstones, vol. I, drawn by Howard Zeiderman

©1985 by the Touchstones Discussion Project

Photo B: The current cover of Touchstones, vol. I

©2012 by the Touchstones Discussion Project

Join the

Join the