By Sharon Thomas

In the beginning, there was darkness. And then three professors from St. John’s College turned on the video camera.

Forty years ago, Geoff Comber and Howard Zeiderman traveled to Hartford, Connecticut, to introduce discussion-based learning to support students struggling in math class. Even with years of experience in classroom discussion, they thought it would help to videotape themselves so they, and other teachers, could learn from their modeling. The trouble was, the lesson didn’t go as planned. The students hadn’t done the advanced preparation they’d been assigned, so Howard had to completely revise the lesson on the spot.

Returning to Annapolis, the two reviewed the video recording with their colleague, Nick Maistrellis. They saw what Howard says he and Geoff had not seen during the lesson itself: “In the vaguest form, a group of otherwise disaffected students worked together to offer some real opinions about straight lines.” Removing the need for student preparation before class had changed the playing field, and using discussion as the medium for exploring content brought about a change in the students’ interactions. That different way of interacting enabled the students to take risks in thinking about math in new ways—together.

That revised lesson was the start of Touchstones.

Over the decades, Touchstones has grown from a lesson in a high school math class to collaborative discussion programs for every stage of life to support learners of all ages in becoming active listeners, skilled collaborators, and more effective leaders.

- First, Howard, Geoff, and Nick developed Touchstones I and II in 1989—high school volumes that teach students how to “map the world” for themselves. They learn not just to turn to text and history for answers but to examine their own thinking and that of their peers for new perspectives and understanding.

- Next came Touchstones A, B, and C—volumes that teach middle school students to apply their valuable thinking as artists, mathematicians, scientists, philosophers, and creative problem solvers, as they prepare to map the world for themselves.

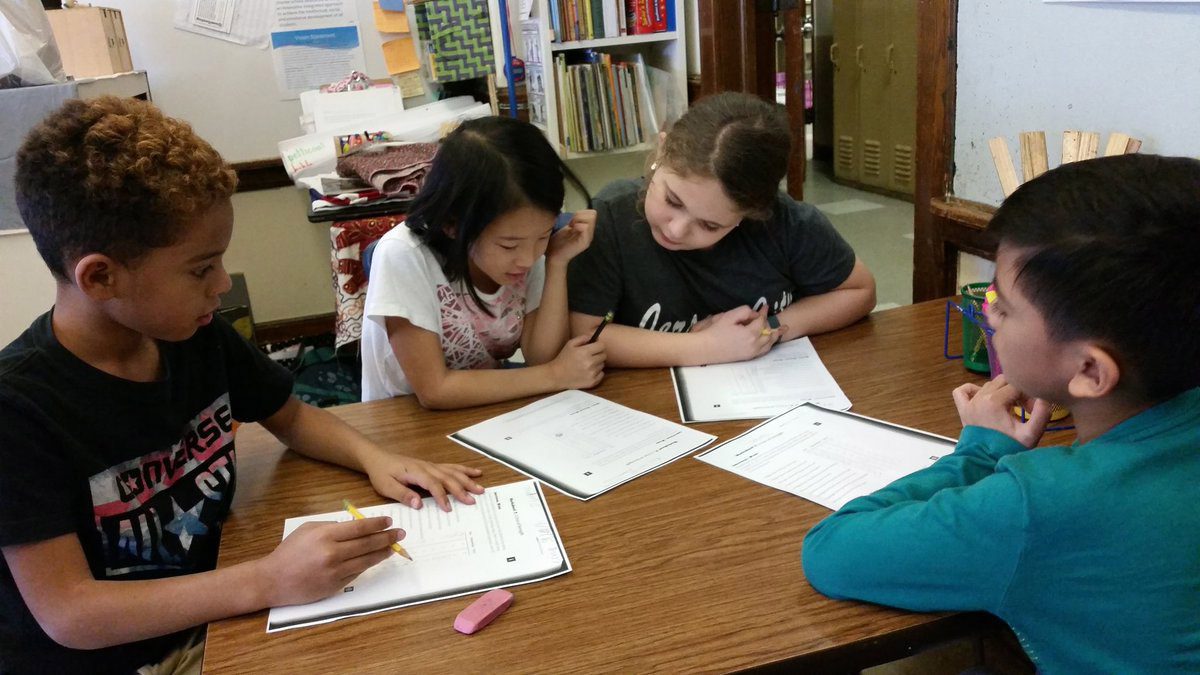

- Then came the cutest curricular series in history, Touchpebbles A, B, and C—discussion curricula that teaches elementary students how and why their thinking is as valuable and necessary as any adult’s thinking is.

Today, Touchstones programs are used in schools all over the world and in every type of school context. But that’s not all.

Touchstones has become a vital part of an array of community programs, often in settings where members of our community may feel undervalued or voiceless.

- Our programs with incarcerated people (both for children and adults) have been in place for decades, affording and encouraging reflective thinking, self-respect, and dignity among people who often feel erased by society.

- Various programs engage seniors in active learning that connects their extraordinary range of experience and knowledge to topics that affect them today.

- Our Completing the Odyssey program helps military veterans understand how skills gained in service are invaluable tools for navigating into and through civilian life.

- Online community programs bring people from diverse ages, regions, and backgrounds to explore and establish common ground.

In 1984, Howard, Geoff, and Nick could never have foreseen all the ways that Touchstones would grow to reach more than 6 million people worldwide.

As Howard says, “Who could have imagined that prisoners hearing about Priam and Achilles mourning together would find useful parallels for themselves in those classical figures and a new way of understanding their own battlefields? Or who would have thought that executives discussing an Iroquois tale would see themselves more clearly because of the story’s strangeness? And who would have foreseen that brain-injured adults would, remarkably, come out of themselves because the shared activities and medium of Touchstones are more accessible to them? Or that indentured children in Haiti would build the courage to ask a question? Or educators in Jordan would collaborate across hierarchical and social boundaries? Or mathematicians and psychologists at NSA listening intently to one another across their compartmentalized methodologies and languages? We could not have imagined it.

Four decades later, our mission remains the same: to support people in learning and growing through collaborative discussion that enhances their ability to see themselves and each other more clearly, compassionately, and equitably. At Touchstones, we are those learners, too. Howard marvels that, “We emerge surprised at what we see in ourselves, as well as what the participants recognize in themselves and their peers—each of us serving as necessary bridges for each other.”

Join the

Join the