By Sharon Thomas, Director of K-12 and Family Engagement Programs

“There is nothing stronger than these two: patience and time. They will do it all.”

Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace

Like most educators, my time in schools as a teacher, instructional coach, and implementation support provider has involved constant change. The curriculum I was handed as a new teacher was gone by my third year of teaching, and that second round of curriculum was gone maybe 5 years after that.

The metaphor of the “pendulum swinging again” in education stings because it’s true—we usually don’t give new programs and strategies the time they need to have the results we want from them, and that perpetuates unrealistic expectations about the speed with which we should see results. Thus, the latest program doesn’t produce a perceived immediate benefit, is cast aside, and the proverbial pendulum indeed swings again. Teachers and school leaders are asked to change how they do their very complex jobs with dizzying frequency.

At Touchstones, we work hard to provide schools with quality implementation support based on implementation research and with individual school needs in mind. That work is complex because no two schools—or teachers or students—are the same. Even when everyone in the room logically understands change and implementation research, the impulse toward the “tyranny of the urgent” still takes over: the desire for immediate, large-scale positive improvement in classrooms feels necessary and realistic (it’s neither), and observing only small signs of change feels inadequate and a lot like failure (it’s neither).

Our concerns for students—whether academic, behavioral, or circumstantial—are complex, and those issues did not develop overnight. Logically, we know that a new program or strategy can’t “fix” those concerns right away or completely, but we still look for signs of “quick fixes” in new programs and in people regardless. This disconnect distorts how we view normal implementation roadblocks (negative staff response, unclear or even worse progress data in the first year or two, etc.) and causes panic that we’re failing at this new thing in which we’ve invested time and money.

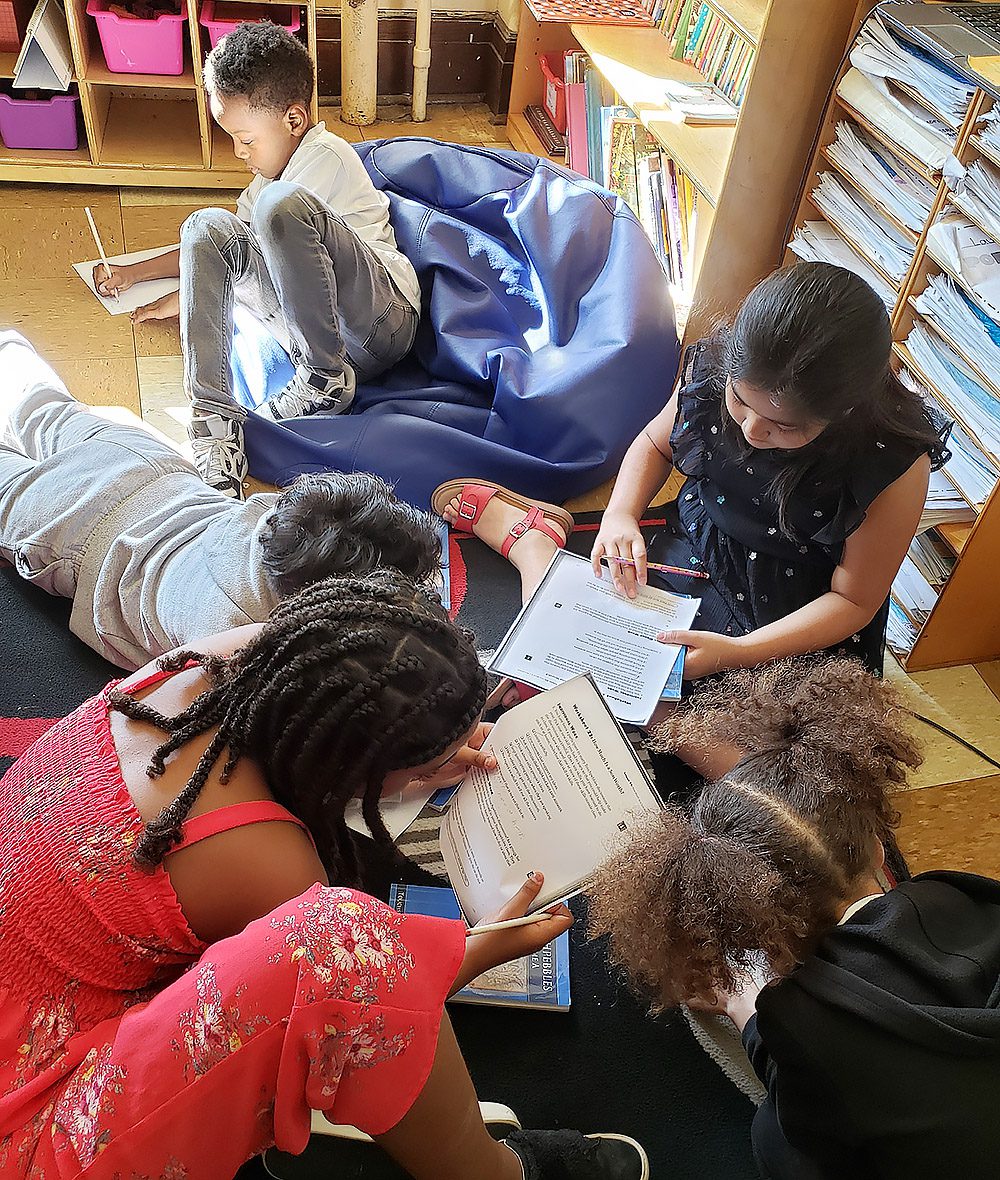

When I was a teacher first implementing Touchstones in my classroom many years ago, I did see some changes in some students right away. I had a few students who had never engaged in whole-class discussion begin to participate differently from their first Touchstones lesson. I saw some students articulate why they participate the way they do in quite sophisticated terms. Those moments were heartening and motivating during those months when I had no idea what I was doing.

As my school district’s Touchstones implementation progressed, as a ninth-grade teacher, I actively looked for signs that incoming freshmen were behaving differently in classroom discussion because of their previous Touchstones experience in middle school. I didn’t see significant, whole group change in discussion after the first year of district-wide Touchstones. Sure, I saw more comfort with the process, and I saw groups move through the four Touchstones stages with more speed and ease each year, but I didn’t see a large-scale, significant shift in their behavior as a group even after the first several years of district-wide Touchstones implementation.

But after that fourth year year of implementation, the difference I observed was mind-blowing. My freshmen entered that year after having four years of Touchstones once a week in grades 5, 6, 7, and 8. In our first Touchstones discussion that year, they were incredibly ready to engage collaboratively and showed skill using multiple strategies to engage other students and perspectives in the discussion. They also showed a deeper ability to reflect on and self-moderate their own participation than I had ever seen before in 14-year-olds.

How did that change happen?

- Those students had teachers in middle school who were dedicated to providing them with Touchstones instruction once a week—no matter how challenging the schedule became.

- The district provided continuous professional learning on Touchstones for teachers and trained instructional coaches and teachers in each building to serve as resources to them.

- Students became increasingly invested in a process to help them learn to self-moderate and lead discussions themselves.

- We all had time. District leaders gave students and their teachers time to figure out what the Touchstones process is and how to use it effectively. We all had time to make mistakes, to backslide (one of the most important phases of real change), and to try again.

Real change requires real patience and steadfastness. Implementing any new program in a school or workplace is challenging because change (like life) is messy. The best thing a leader can do to bring about real growth and improvement is to not cave in to the tyranny of the urgent. What leaders need to do is to replace urgency with patience and replace seeking perfection in staff members who are learning something new with encouraging reflection instead. Leaders need to flexibly troubleshoot concerns, and, yes, stay calm when reversion to old habits happens.

The perceived chaos, the complaining, the backsliding that comes with anything new—they are all normal parts of change, and true leaders understand that and are willing to navigate (and sometimes simply ride out) those barriers to bring about significant growth.

No lasting change occurs without leadership that is willing to create an environment that embraces how complex and difficult the change process is. The world would be an even more amazing place if deep change occurred quickly and easily, but that’s not how human beings learn, and it’s not the world we live in. Humans most effectively transform ourselves through day-to-day commitment, support, and reflection. That is the path not only to implementing Touchstones (or any other program) well; it’s also the path to creating the collaborative world that Touchstones invites us all to envision and bring to life.

Join the

Join the