Beyond Socratic Seminar: How Touchstones Builds Skills to Face the Future

By Howard Zeiderman, Co-Founder, and Stefanie Takacs, Executive Director, Touchstones Discussion Project

Over the years, many classrooms have introduced seminar-style discussions to make classroom discussion more student-centered. These discussions typically involve a selected text that students read and then discuss in a forum guided by the teacher’s questions and feedback. Unfortunately, these structures have not been as successful as one would hope in addressing the central issues facing today’s classrooms: cognitive passivity, student disengagement, and polarized social discourse.

Certainly, there are some accomplishments from these seminars. Students discussing important concepts with each other is a well-documented part of research-based literacy practice, and some schools have seen literacy gains for students tied to those seminar programs. However, even those apparent gains are usually evident for students who were already considered “high achievers” in the traditional academic sense. In addition, if one examines the rates of student participation in such seminar programs here and abroad (even among high achievers), one typically finds that 25% of participants are very active and dominant, 25% are silent, and about 50% are as frequently disengaged as they are engaged. These percentages are also frequently related to gender and race, and thus these seminars can reflect existing, larger societal issues around who in a group is perceived as “allowed” to have voice.

In the end, these seminar programs have not changed the discussion dynamics in most classrooms. The roles students play in seminar settings generally reflect those individuals’ roles in traditional lessons. The format of these seminars is still heavily teacher-centered, which means the teacher remains the source of legitimacy and correctness. Typically, teachers always choose the text in play, they choose the questions that students discuss related to a given text, they decide who gets to speak by choosing from among students’ raised hands, and they are the arbiters of “right” and “wrong” responses. Discussing text alone, with the teacher positioned as the ultimate authority figure, can help the teacher to feel that discourse is orderly and under control, but it doesn’t teach students how to navigate difficult issues with each other.

Thus, a “seminar” discussion often means that the very profound intellectual and social problems these initiatives were meant to address are frequently reinforced or even exacerbated. A discussion environment can change traditional discussion dynamics, but teachers and students need a process that has inclusive discussion as its focus (not with a text or teacher-determined topics as the focus) to be able to develop the skills necessary to engage everyone. That process is Touchstones.

What is an inclusive discussion? It is one in which every participant has a legitimate voice, where every voice is essential to its success, and where there are no subgroups or factions that exclude some speakers. It is one where all members, including the leader/teacher, become increasingly aware of the factors (personal, institutional, and cultural) that influence their thinking and close them off to the thoughts of their peers or the authors they read. And it is one where, after a guided period of development, leadership is shared among all members of the group.

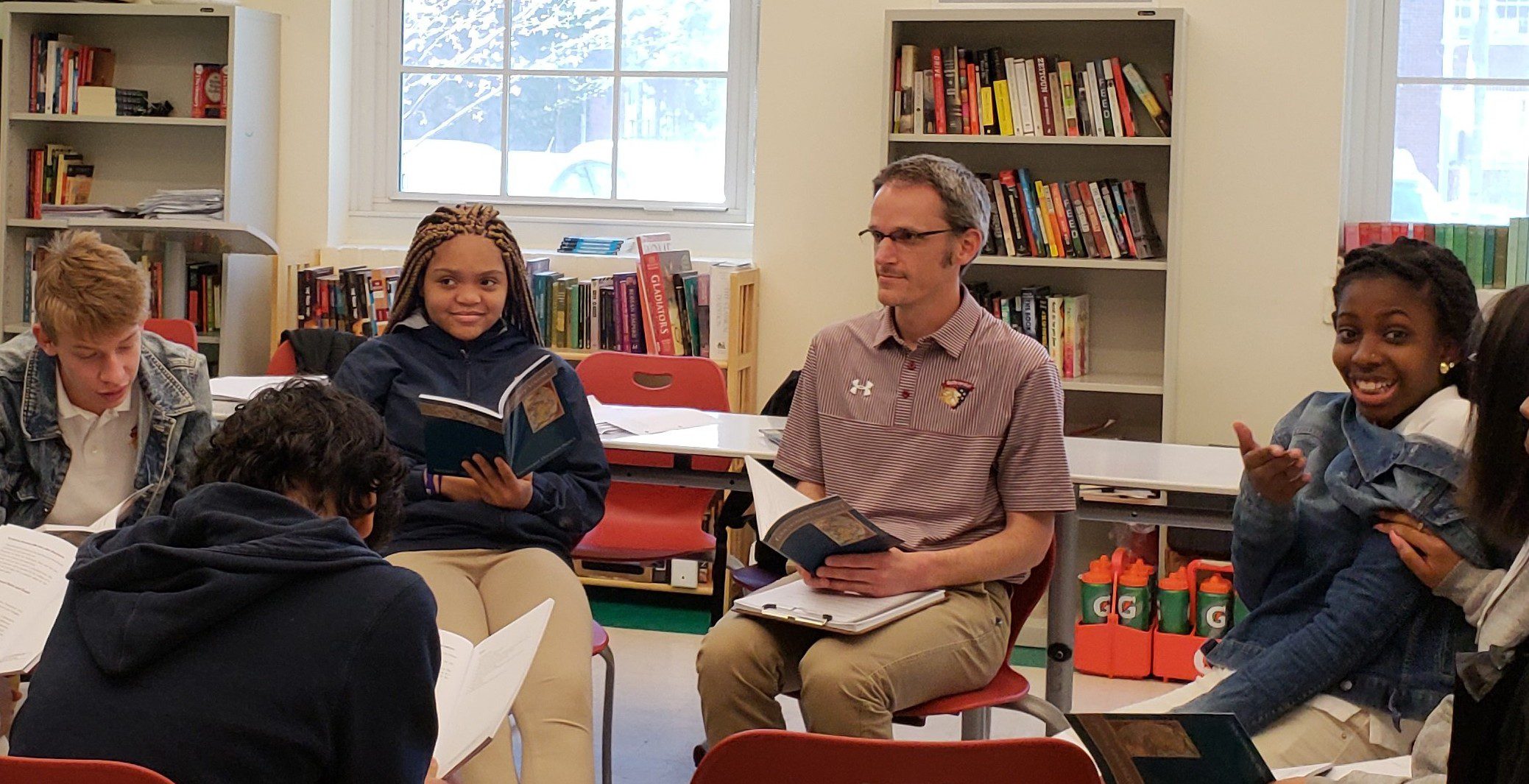

Touchstones is a once-a-week, hour-long program that achieves these results for all students, regardless of their historic academic performance. Touchstones develops new attitudes and skills through a carefully structured program involving strategically selected texts that function as tools (or “touchstones”) for increasing self-reflection. The process also involves self-assessments and group assessments of discussion dynamics and a sequence of leadership activities through which power and responsibility are shared. The participants gradually move through a four-stage process to become a fully inclusive discussion group. The result of this program is a group of participants who share in leadership and undertake collaborative exploration with their peers and their discussion leader.

Although its approach to discussion is innovative, the Touchstones environment reinforces many traditional classroom skills. Students improve in critical reading, articulating their ideas, citing evidence, and demonstrating empathy as they progress in the process. Most crucially, however, they form a new set of skills and attitudes, ones that we now recognize are fundamental in the landscape of the 21st century. These are skills and attitudes we all need to be more fully human in our globalized and technological environment. In short:

- It is no longer adequate to develop good or even excellent students. All students must become teachers. They must be able to teach themselves and others as new kinds of knowledge constantly emerge, knowledge that is required in our lives and work.

- The solutions to all problems require collaboration from diverse professions, backgrounds, talents, ideologies, and faiths. We must move to a new mode in which we view thinking as a collaborative activity.

- All problems are new and unique. Problems such as climate change, financial crises, pandemics, and terrorism cannot be solved or even navigated with previous models. These issues require understanding our own assumptions and biases so that we can more fully understand and address the future’s specific and unique circumstances.

- Power and responsibility must be shared by all of us as workers, professionals, and citizens. We must all learn to exercise power, to share it with others collaboratively, and to relinquish it to others when appropriate.

Touchstones is now in its 41st year. The first decade of the project was spent examining the possibilities of this pedagogical mode in many pilots and recognizing the barriers that are obstacles to it. The second decade was spent designing and creating more than 40 individual titles for use in grades 2 through college and also in organizations and institutions. It involved developing detailed guides to prepare teachers and leaders to undertake this new mode of engagement. The third decade was devoted to refining and perfecting approaches and to preparing staff development resources for teachers. Our fourth decade saw us expand and bring to scale programs for people across the lifespan, including new programs for military veterans and the people who love and work with them and college students in first- and second-year seminar courses.

Now in our fifth decade, we continue to create and support programs that are responsive to our constantly changing and evolving world, one that is globalized, technological, replete with dangerous disparities and inequalities, and insidiously factionalized so that we can ensure that human beings navigate the world and its problems together, with respect for each other and for the enormous challenges we all face.

Touchstones uniquely prepares all students for a fully engaged life in the world. And, as we have demonstrated for more than 40 years, the use of Touchstones in schools and in other institutions and communities, including corporations, government agencies, prisons, and senior centers, also serves to enlighten, guide, and humanize our approaches to working together as a global community.

Join the

Join the